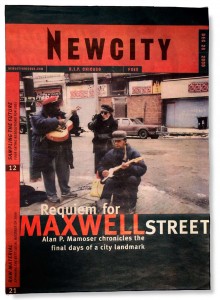

My article Requiem for Maxwell Street was published in New City, December 28, 2000. It provoked an interesting letter to the editor from Chicago artist John Sibley. An article about my small role in it appeared in the Chicago Flame in Feb 1999. The original text of ‘Requiem’ as submitted follows below.

My article Requiem for Maxwell Street was published in New City, December 28, 2000. It provoked an interesting letter to the editor from Chicago artist John Sibley. An article about my small role in it appeared in the Chicago Flame in Feb 1999. The original text of ‘Requiem’ as submitted follows below.

The Final Days of Maxwell Street

It’s hard to believe, but a little bit of Maxwell Street still stands in 2001. The city and UIC have done away with most of it. They removed the outdoor market six years ago – the market that filled the streets around Maxwell and Halsted every weekend for 120 years. They just lifted it over the Dan Ryan expressway and set it down six blocks eastward, where it runs a long line of stalls down a barren stretch of Canal. It’s a common flea market now, with some pretty tasty Mexican food on offer. But the place exudes impermanence; its soul is vanished.

“It was so beautiful there, with all of the people and the buildings around,” says Florence Scala, who fought against UIC forty years ago to save another nearby neighborhood. “They’re sick!” she says, referring to the old nemesis.

But the buildings are actually still there, running the length of Halsted from Maxwell Street to Roosevelt Road. And the old merchants are still around, too, although not for long. These guys go back together forty years or more, and their fathers before them. Saul Federman is still in Al-Robb’s, and up the street is Alan Federman in Adam Joseph’s (Saul claims no relation). Across the street is Neal Silver in Century Fashions, with his rambunctious coven of salesmen. They’ve been in these buildings through five decades of fashion and still make a good living. It’s not for lack of customers that they’re going away.

These guys are authentic Maxwell Street: go in and bargain with them, there’s no price tag on the goods. And after you’ve haggled a bit you find out they’re friendly and you get to know them. In the old days the merchants on Maxwell were famous for putting “pullers” on the sidewalk, who stood out there and strong-armed you in. They’re a little gentler now in plying the merchant’s ancient craft, but their genius does not lay in assuaging customers with sweet words. “For you,” they say, “we’ll make a good deal…,” and they name a price. Then they fit you, mark the garments up and send you down the street for free sewing at a tailor shop called Tino’s. It was a Maxwell Street tailor, Hal Fox, who in the ‘40s designed the world’s first zoot suit. The merchants still carry good stuff for Saturday nights: glowing shirts, dress hats, classic cut suits and polychrome sweaters. At Century Fashions it all comes in XX-Large.

Jim’s Original is still busy on the corner, along with his cousin’s stand just a door away. It’s not closed a day since 1939, when Jim Stefanovic came from Macedonia and began serving up the famous polish heaped with smoking onions. “He didn’t take a vacation for twenty years,” says his son, Joe, “and he learned to speak Hebrew so well that most folks thought he was Jewish.” The gentile sausage seller served his non-kosher delights to Jewish merchants, famous and non-famous bluesmen, and millions of others until his death in 1976. One busy labor day weekend the stand went through 2,000 dozen buns, which Joe figures comes to about 20,000 polishes served in three days. He still follows his father’s recipe: “We check the delivery every week, make sure of the quality of the sausage casings and the meat. There’s no garbage in them. Some places put garbage in them. But ours are good beef. Heck, even some Polish people think it’s the best polish they’ve eaten.”

The two stands sit in the midst of commotion on Maxwell and Halsted. It’s as if the market’s old bustle were condensed to a corner. Jim’s grills come right to the sidewalk, just behind thin walls and those smeared plastic windows that release a torrent of steam when they’re opened in winter. Foot merchants crowd around hawking socks, gold chains, posters in frames, the lurid porno tapes; all those little accoutrements that once adorned the outer edges of the great marketplace. The white-aproned cooks stand just above and hand out food piping hot, 24 hours of the day, all days of the year. And the whole scene is crammed on a gritty, lopsided sidewalk at Maxwell and Halsted – nowhere in the city is there a more rotted piece of useful street.

It’s all an afterglow of what was here, and soon these last vestiges are going away. UIC is taking it all now. They’re scattering the old merchants and bringing in new ones, in new buildings, with a new set of pre-approved stores and restaurants. The great urban university is building a “24-hour community” at Maxwell and Halsted. Industrious new residents will stand on new sidewalks. UIC believes there is not room enough for them and for Jim’s 24-hour polish stand. Jim’s can stay, but its going inside; the stand will be gone forever.

Across the corroded stub of Maxwell Street a new utopia rises. A skeleton of thin metallic beams forms the new dormitory, right on the place where Nate’s Deli stood! Concrete now covers the tree where the bluesmen played, where for years they plugged in their amps to an outlet behind Nate’s. Serene ball fields unroll for a whole block southward, over the ground where the outdoor market flourished. Its fence-surrounded now and lighted at night like a jail compound. UIC not only moved the market; they erased its existence. Now the same will happen to the old merchants and their old buildings crowded along Halsted. They have just a few weeks left.

Stuffed between the polish stands is an inconspicuous, rather oddly-shaped little shop with a brown metal roof holding a happy orange sign: Heritage Blues Bus Records (Down Home Music). A stereo speaker blasting the blues announces when the store is open. Go below the rolled-up metal door, through the dusty glass displays, and soon your eyes fill with blue walls and the strange sight of hay bales around a narrow room. On the bales are cases and cases of tapes and CDs. Here are the Reverend John Johnson and his wife, Marie, purveyors of tapes and records for thirty years in the Maxwell Street Market. They have Blues, they have Gospel and Soul, they have dusties of all the artists; name a song and Rev. Johnson will find the tape it’s on.

For a long time they came here in a bus, a big school bus that was painted, naturally, blue. These days, the market gone, the bus broken down, they’ve settled into a less itinerant life, sitting and watching the world go by, the world as it is on Maxwell Street. Rev. Johnson won’t mind seeing the place get cleaned up a bit, but he would like to keep his store around. “I keep this place here not to make money. There’s no money in it,” he says. “I keep this place here, for the presence. It’s for the memory of all the great things that happened here and all the great music coming out of here.”

Perhaps more than anyone alive, Rev. Johnson knows the fading soul of Maxwell Street. He knows the source: “There were the Jews here first. Maxwell Street belongs to them. Through their faith in the one Lord God they built this place and made it great and made it a place, where people of all colors came together…”

A Place Full of History

For long decades humanity swirled around here, packed in tight quarters. Jewish merchants were prevalent. They were immigrants arriving in a west side already crowded with workers in the 1880s. Their response with a market was spontaneous; nobody planned for it. It came with the people, a market of the Old World blooming again in the strange streets of the New, outdoors in the open air. They set up carts and stalls along the narrow length of one small street and sold all manner of wares and clothes. Soon Maxwell Street was known as a market street, and City Council obliged with official approval in 1912.

Generations of them from Europe, from the South, more lately from Mexico, came to a kind of Ellis Island in the Middle West. They came through and they moved on to their own neighborhoods. It wasn’t a place where people stayed around for long. But each nation left something of great worth behind. Irish and German workers built the brick churches of St. Francis and Holy Family for the Catholics, and a small brick church on Union Street that later became a synagogue (it’s now called Gethsemane Missionary Baptist Church). Jewish immigrants made the market street. Blacks from the south gave a new style of music: the urban electric blues.

It was remarked of the American worker that he dressed well, even on his wages, and immigrants could put themselves in good clothes for Sunday, in jackets and shirts and dresses. These were to be had on the west side at Maxwell Street, where apparel lay stacked on the tables, where quality was known to be pretty good and prices could be bargained for. All creeds, all races, and just one color: green. The color of money. It was key to the market’s long success. For the market stood between neighborhoods, on the near west side, in that part of the city that was a transient place and port of entry. Nobody stayed on the near west side for long. And being between places, nobody ever claimed it. Here blacks and whites mingled freely, spoke, became friends, long before Civil Rights, in days when the Loop was all white and the near south side only black. Here Jewish merchants met the bluesmen. They strung electric cords from the stores to the street to play guitar for the market crowds, and the city air filled with music of the Delta.

“There were crowds of people coming down here, thousands…you couldn’t walk,” says Alan Federman, remembering his boyhood on the street. The mixture of people was so rich that visitors could only marvel. When Simone d’ Beauvois walked through in 1947 she stood amazed at the crowd and the clamor, the music, the preaching and the dance, the banter of all peoples in this American marrakesh.

More prosperous merchants eventually moved around the corner up Halsted Street, which is a wider and more prominent avenue. They built new stores, fine stores of glazed brick and carved ornament in modern art deco facades. One can safely say of these buildings, they just don’t build them like this anymore. They have great display windows of thick glass that curves round and beckons inward to deep-set glass doors. Gray sidewalk gives way to passages of once-shiny mosaic tiles in orange or emerald green. Within are deep, high-ceiling rooms. They are not quite elegant, but refined, useful, earnest in function and full of appeal.

These faded edifices still stand along Halsted Street, the offspring of Maxwell Street merchants. The merchants will tell you how their fathers started on Maxwell Street, how they worked in the stores on Maxwell as kids before going to Halsted, and how their businesses thrived in both locations. They talk about all the old stores, and their owners long dead, and the good eating places. There was Lyon’s Deli and Leavitt’s Deli, where pickle jars stood on wood floors and great sandwiches were served over the counters.

As a boy on Maxwell Street, Nate Duncan learned to make pickled herring. He learned in Lyon’s Deli by carefully watching the kind Russian wife every day. Then he worked for the family faithfully from 1947, and took over the deli when they retired in ’72. A black man keeping a kosher deli never struck anyone as strange on Maxwell Street, and for decades his food nourished the bluesmen. “We had them all coming in there, and the great ones, Little Walter, Junior Wells and the rest,” says Nate. “But my store was like, so…friendly. You walk in and you’re with friends, didn’t matter blacks, whites, Mexicans. A guy could walk in for the first time and it was just like he had been there for thirty years.”

It is this special friendliness that is universally remembered by everyone who went down to Maxwell Street. Talk to anyone who knew it, anyone of any color who went down there on Sundays on a streetcar or bus. Their memories are joyful ones, of the crowds, and the hustling merchants who never left you with a bad deal even if they got the better part of it. There is never a dour comment, never an ugly recall of racism. What stays in peoples’ minds is the friendliness of the place.

An Academic Intrusion

The outdoor market stretched the length of Maxwell Street until the Dan Ryan came through. This slab of concrete sweeps up from the south on high stilts, then slopes down fiercely to pierce the little street before swerving off in a snaking curve past the Loop. It came in 1962 (see the classic documentary on Maxwell Street in the early ‘60s, And This Is Free…). The weekend vendors migrated to open lots along the west side of Halsted that were conveniently cleared of slum housing; they took up two blocks from Maxwell Street southward to carry on the outdoor bazaar. The bluesmen set up under the tree behind Nate’s. Was it an elm tree, or maybe an oak tree? Opinions differ among old-timers, but it was a big tree.

And so the market went on, under the benevolent care of Fred Roti and the other first ward aldermen who ran things in traditional fashion. The market master worked for the city, nominally, but really worked for the ward. The store merchants called the first ward when they needed a trash barrel or wanted streetlights fixed, and things got done. The precinct captain would occasionally drop by to visit the merchants and tell them about a special collection or fundraiser for charity. He always received a gift in a small envelope, with a little contribution to the Democratic committee.

“He always did a lot of good for people there, Fred Roti,” says Joe Stefanovic, “…he got indicted, but when he got out he did a lot of good for people.”

Under such management the market gradually descended into a kind of benign neglect, and by the ‘70s it had become a pretty shabby affair. But the place remained ever lively. When Aretha Franklin played the waitress in Nate’s for Jake and Elwood Blues, in ’79, Maxwell Street was a customary destination for people from across the city, drawing many thousands on a Sunday. It was a sprawling bazaar spread over concrete fields, with the bluesmen playing, the polish stands steaming, folks coming from mass at St. Francis, and the blue bus parked along Halsted. A neighborhood to the south called Pilsen was filling with the latest immigrants, now from Mexico, and the market gradually began to take on something of a Latin feel.

Benign neglect engendered some problems, of course. The weekend market was under-policed, hot goods proliferated, and the place acquired a reputation for criminality. It was said, you get car parts stolen on Friday, and you go down to Maxwell Street on Sunday to buy them back. Famed journalist Ira Berkow came out with his book Maxwell Street, Survival in a Bazaar in 1977, and doom was forecast. Berkow had his eye on the expansionist university to the north. Yet the market remained mostly honest and never lost its friendliness. Even the porno tapes guys wouldn’t hurt you; you just told them “no” if you were not interested and they went away.

When UIC took up quarters along Harrison Street in 1964 (near a place where expressways come together in a lovely Circle), the administration promised to not go south of Roosevelt Road, down into the market area. The university’s president said so in a letter to the city (a letter dated April 17, 1961). But the university’s master plan showed a visionary, ultra-modern campus expanding south to the viaduct at 15th Street. Their land ambitions were only momentarily fulfilled as they settled into the spacious, specially made concrete monstrosity for which one neighborhood had already been obliterated. Most folks down on Maxwell Street knew their days there were numbered when the university came in. It was apparent to anyone who saw how they tore out a whole neighborhood. About two decades later the ambitious administrators moved in to complete the original plan.

Poor Circle Campus, unlovely little brother of the big school downstate, was fated to the humble task of educating working class families’ first college generation. Circle took up the good task of giving college education to thousands of urban youth, but it didn’t get much time in the academic limelight. As recently as 1998, the provost of the university stated that UIC would become another Harvard, such that a talented kid deciding where to go would find an equal choice between UIC and Harvard.

This lust for recognition helps to explain their land ambitions. Administrators naturally felt some identity crisis as they looked out from their wood paneled offices on the twenty-sixth floor of concrete, stalinesque University Hall. They changed their name to UIC, they tore out some of the concrete and put in flowers, but these moves were just preparatory to their grand work of gentrification in the area to the south.

Alan Federman takes the philosophical long view on the whole thing, saying, “The university isn’t a person – there’s always a lot of people rotating in and out of those positions. You can’t fight it forever. I’m getting old, but the university is just growing and getting more modern, that’s all. Call it progress.”

Progress came quickly in the late eighties, a few years after the break up of the old first ward organization. A new mayor came to power and a new alderman came in to govern the Maxwell Street area. Under him benign neglect became definite hostility. The market declined precipitously; the place became positively ragged. Now merchants called ward headquarters for help and were told, with some heat, not to bother the alderman. The rest of the story is laden with depressing detail but may be summarized in a sentence: in less than ten years UIC went from having little presence south of Roosevelt, to gaining ownership of the market’s land (awarded to UIC by the city council in 1994), to having the city cover the entire area with a TIF district in 1998.

The weekend vendors never got well organized for the battle, a battle that had really been going on for thirty years and promised to be interminable. There was some organizing and some protest, a couple of marches on City Hall, but it folded pretty quickly. A new place was offered on Canal Street and some of the vendors took up the offer. Says Carolyn Eastwood, who worked to organize the vendors: “Anytime you get something as free wheeling as a market…everybody wants to do their own thing. They’re essentially individualists, that’s why they’re down there (in the market). So organizing was tough.”

UIC came in, built the ball fields, demolished Nate’s Deli and cut down the blues tree. The university bought up the remaining old buildings along Maxwell Street and let them go to rot, vacant and unused. When it came time to get the TIF, UIC’s developers went around showing pictures of these buildings to demonstrate how the area was “blighted” and in need of public help. The developers never mentioned that UIC itself was their owner. The TIF will generate revenue from 850 units of private housing, funding (they hope) some academic buildings in the northern portion of the site.

The story finally goes back to the alderman, the same alderman who so effectively facilitated the market’s handover to UIC. He returned to private life and just recently experienced some economic good fortune. Last year his firm was named by UIC as exclusive broker for all residential sales in the new University Village. That’s 6% commission on each sale of the planned 850 units; estimates put his potential earnings at $12 million.

Requiem For Maxwell Street?

We are left to ask UIC, simply, why? Why eradicate a place that for 120 years has so enlivened the city? One might think that a university would embrace and enhance an irreplaceable cultural asset. The businesses are still healthy and draw customers from across the city. The merchants’ buildings are still good, needing just a bit of fixing up. Even in these last days, as the shadow of final doom hangs over Maxwell Street, it remains, strangely, vibrant. These friendly characters keep coming out of the woodwork, folks who’ve in one way or another fallen in love with Maxwell Street. They believe in its resurrection.

There’s Merlin McFarlane, who reconnoiters the area each day with a broom and a trash barrel on wheels. Merlin curses the endless litter, then smiles behind his tussled hair and big glasses and returns to his life’s work. And a few of the bluesmen still come down to play on occasional Sundays. For a couple of years their gigs happened on the abandoned corner across from Jim’s. They stood on a wood platform before black rail ties sticking up from the ground as the letters M A X. Last fall UIC cleared this place out and surrounded it with metal fencing, but the musicians still come. Recently local musicians Bobby Davis, James Washington, and a harmonica player called Mr. H have showed up. One admirer says of Mr. H, “He’s a white man who plays harmonica like a black man, because he was raised on Maxwell Street.”

These guys are the unsung musicians of Maxwell Street, the ones who didn’t get famous like guitarist Jimmy Lee Robinson and band leader/organist Piano C. Red. They put out the hat and play for your cash, in the long tradition of the street. Jimmy Lee has fond childhood memories of the street’s now vanished kosher hot dogs, although he long ago became vegan. He sees all potential evil in the universe deriving from human digestion, and everything that is good having a mystical source on Maxwell Street. He sometimes goes into Gandi-like fasts for the salvation of the street; two years ago he fasted for 90 days.

There are also the activists, a little oddball group of them who worked to save the buildings as a testament to Maxwell Street. They formed a preservation coalition, consisting of an architect, an educator, a writer, a few graduate students, and two relentless torchbearers who would not let the place die in peace. Bill Lavika, a structural engineer, has been rehabbing buildings on the West Side since he got back from Vietnam thirty years ago. Steve Balkin, professor of economics at Roosevelt University, is a specialist on open-air markets worldwide. And there is Lori Grove, who lovingly catalogued the architectural ornament on each of those old facades. Lori and the coalition came heartbreakingly close to getting Maxwell Street on the national historic register, twice having their bid unanimously approved by an independent panel, only to have it twice vetoed by the politically-controlled state preservation official in Springfield.

Over the past four years the coalition carried the cause around the world on the internet and to the highest echelons in city hall. They reached the mayor’s secretary and won his sympathy before he got fired. They forged an alliance with Oscar D’Angelo before his fall from favor. Finally, the mayor declared that he wanted “a real Chicago look” down on Maxwell Street. Things began to roll, and within a year from the spring of ’98 to the spring of ’99 the city paid two separate groups of famous architects to draw up plans for preservation. The plans showed the university’s large new buildings gracefully interwoven with the restored stores on Halsted, and the preservation coalition touted them loudly.

UIC administrators apparently never fathomed the depth of attachment, never foresaw the outcry of diehards who would try to wrest from their hands this one small scrap of the urban fabric. They agreed verbally, then reneged, and then rejected the alternative plans. But not totally. Slowly, reluctantly, under pressure they came to acknowledge that there was indeed a Maxwell Street, a place with a history worthy enough for commemoration. In a 1999 TIF development agreement with the city, UIC promised to keep intact eight whole buildings (not the merchants, just the buildings), and to preserve the facades of twelve others. The facades are to be pasted to the exterior of a new five-story concrete parking garage, slated for the corner of Maxwell and Union Streets. This façade cover-up idea received withering criticism from the city’s most noted architecture writer, while the coalition takes little consolation from the small UIC compromise.

Folks like these just keep coming out of the woodwork around Maxwell Street. They’ve made its dying to be like its birth and its whole long life: spontaneous, unpredictable, surrounded by clamor to its last moment. And perhaps that is what UIC fears the most, that if it doesn’t get stamped out entirely it will just keep coming back to life. It would always stay a little bit outside of anyone’s control.

Rev. Johnson can’t help recalling the long history of Maxwell Street as he sits with his wife in the small store on a Saturday, watching the parade of passersby. They are resigned to leaving their small store soon, thinking about retirement now that thirty years of work in the market is coming to a close. “This place was deep in spirit,” he says, “such that great things could always happen here. The music itself is the witness. The music is always joyful, even when its blues. All those years of all the terrible racism in this country, and there is not one trace of it in the songs.”

Maxwell Street still lives! It is the cry of the preservation coalition, and it’s accurate. Maxwell Street cannot be written off yet, and may never be forgotten about with living memories as strong as these. Rev. Johnson has purchased a new bus, a small one now, and he and Marie carry blues tapes over to the new market on Canal Street each Sunday. He talks about expanding his stock in the new market, getting some stuff in salsa. But blues will remain his main line. He also plans to drive south in the bus, back to Mississippi. And he affirms that, very soon, he will paint the new bus blue.

Visit the Maxwell – Halsted stores in their final days there. The merchants will be putting on closing sales (no price tags, of course). And see the web site, http://www.openair.org/maxwell/preserve.html

0 Comments