A tribute to a friend, in Living Blues magazine, March 2022, pp. 75-76 | download

see also, Requiem for Maxwell Street

John W. Johnson, 1937 – 2021

“Being black, being born black, being raised black…. I came into it when I first started breathing,” said Elder John Johnson of the Blues.

It was his last conversation with me before his death in November at age 84. He was a dear friend.

John W. Johnson, owner of the iconic Maxwell Street Blues Bus, had much to say about faith in the One Lord, about Blues, and about being black in America. Far from being cynical, he spoke a lot about the evil of racism while exuding a deep love for his country.

Rev. Johnson died peacefully at home in Indianapolis on November 5. He is survived by his wife Marie Johnson, brother Merrill L. Johnson, sister Sharon M. Johnson-Nugent, brother Michael P. Johnson, and a host of grandchildren, great-grandchildren, cousins, nieces, nephews, great-nieces and great-nephews.

He was born on July 23, 1937 in Elsberry, Missouri to Wallace S. Johnson and Dorothy L. (Douglas) Johnson. He and his siblings enjoyed playing on their Grandparents’ farm in Elsberry before moving to Omaha, Nebraska with the family as a young boy.

It was at home, from his parents, that he first heard and came to love the Blues. As a young man he served in the US Army. Later he owned and operated clothing and music stores in Omaha, Minneapolis, Seattle, and Chicago. He spent his last years with his loving wife in West Memphis, Arkansas. He and Mrs. Johnson wanted to be there, close to the source of the Blues.

John Johnson loved the Lord and began preaching the gospel in his early years. He is known to many as Minister and/or Rev. Johnson.

At Maxwell Street

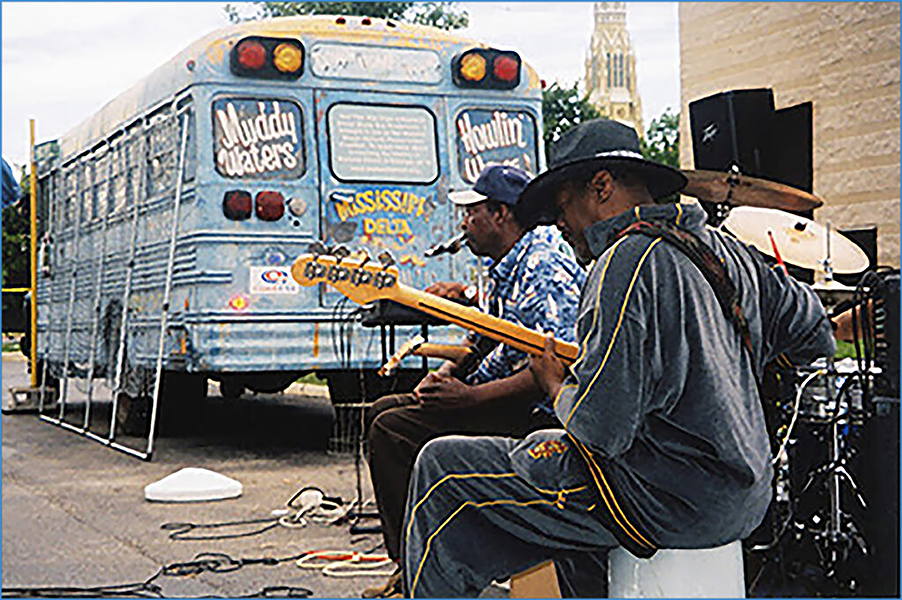

He also loved the Blues. In the 1970s and afterwards, he sold Blues records and tapes on Sundays. He took his Blues Bus, a converted school bus painted blue, down to 14th Street at the Old Maxwell Street Market in Chicago. His big, bright blue bus became a well-known part of the bustling Sunday market, which stretched along little Maxwell Street to east and west of Halsted, on Chicago’s near west side for many decades.

Maxwell Street is known as the birthplace of Chicago Blues. Rev. Johnson and his bus added to the scene. He hooked up big speakers that sat on the trunk of the bus, blasting the music down the street. Customers came to him from all over the city. They would just name a song and Rev. Johnson would find the cassette or CD for them.

After the market’s forced removal in the mid-90s, he operated and owned a Blues records store on Halsted St., just 25 feet north of Maxwell Street. His store, called Heritage Blues Bus Music, was sandwiched between Original Jim’s and Maxwell Street Express, purveyors of the famous polish hot dogs.

Elder Johnson knew many Blues musicians and did not rate Blues music on a plane different from Gospel. He appreciated both and saw the common roots of both.

He was a mentor and close friend of Alligator Blues recording star Toronzo Cannon.

“Rev. Johnson was very encouraging to my journey in the Blues,” says Cannon.

“Every time I would visit him we would have at least an hour or more of conversation about the Blues. One of the most memorable things he done for me was to give me a Luther Allison CD called ‘Where Have You Been? Live From Montreux.’

“He told me to listen to this music and hear what he’s doing. I did just that and it opened up my playing immensely. He saw something in me and my conversations with him that I didn’t see. I’ll never forget his kindness to me as a young man just discovering the Blues.

“He’s The Chicago Blues Man!!” says Cannon of the late Elder Johnson.

Another young man who was mentored by Elder Johnson and later came to prominence on the Chicago Blues scene was Barry Dolins.

“I first met Johnnie Johnson in the mid-sixties when he would be selling LPs from the back of his green Pontiac station wagon,” says Dolins.

“He hooked his KLH sound system to the electric supplied by Loyal Drug at 1301 S. Halsted. So while he played everything from Lightnin’ Hopkins to Gene Ammons, I would be selling sunshades. And Arvella Grey was playing his steel guitar just to the south of me in front of Just Pants clothing store. Quite an education!

“Johnnie would also drive his ‘36 black Buick to the street and provide me with a sound track of my youth during the weekends. His full time gig was owning an 87th street Haberdashery.”

Dolins went on to a prominent role on the city’s cultural scene promoting the Blues. He worked on a National Endowment grant where the “Maxwell Street Memorial Day Gospel and Blues Bazaar” helped kick off the initial blues festival under Mayor Harold Washington’s administration. He administered the Neighborhood Festival program as well as coordinated the Chicago Blues Festival for many years. He retired as Deputy Director of the Mayor’s Office of Special Events in 2010.

Currently, Dolins is serving on the board of the Mojo Museum, developing Muddy Waters’ home in Chicago’s Bronzeville into a community museum.

Another friend and longtime advocate of the Maxwell Street Market is Professor Steve Balkin, who admired Rev. Johnson for his devotion to the music.

“I bought Blues records from Elder Johnson at his Blues Bus in the old Maxwell Street Market years ago,” says Prof. Balkin.

“I remember that he loved Gospel music but also Blues music and thought both were gifts from God. In the 1990s he owned a record store called Heritage Blues Bus music, also in the Maxwell Street neighborhood. He decorated it so it would have a southern down-home feel. He put a bale of hay outside in front…I think he would have had a live mule at his record store if the City would have allowed it.

“He seemed to always spread the culture of southern Blues and Gospel wherever he went.”

A spiritual son

I first met Rev. Johnson at the market in the mid-90s. By then the big Blues Bus was broken down and he and Marie were driving about in a smaller bus. They had their little store on Halsted and went in the small bus every Sunday to the new Maxwell Street Market on Canal Street. A big speaker still went on the trunk!

He was very kind to me, he called me his son, his ‘Spiritual son, a son of a different color.’

We had long talks about the Market, about the music, and about faith in the Lord. He saw his work to purvey Blues music as a divinely ordained mission. He saw the Blues Bus as an instrument of that. I bought a lot of music from him, and he always encouraged me and gave me good advice for life. He was always positive, always optimistic.

He had a deep sense of himself as a Black American. He had deep respect for other peoples too. And perhaps more than anyone, he knew the soul of the Old Maxwell Street Market as a place of many peoples. He knew its source: “There were the Jews here first. Maxwell Street belongs to them,” he once told me.

“Through their faith in the one Lord God they built this place and made it great and made it a place… where people of all colors came together…,” he said.

Prof. Balkin and other members of the Maxwell Street Foundation have tried to preserve Rev. Johnson’s original Blues Bus. Unfortunately the old bus deteriorated over the years and was vandalized. So they decided to cut off its rear five feet, to be rehabbed and become part of a permanent Maxwell Street exhibit somewhere. They’ve been in talks with the new president of the Chicago History Museum to see if the back of the bus and a permanent Maxwell Street exhibit can be placed in the museum.

As Prof. Balkin told me, “New Orleans has the French Quarter and Memphis has Beale Street, so shouldn’t Chicago continue the Blues Trail with a permanent exhibit on Maxwell Street at one of our major museums?

“That could promote all the local clubs and places that remain of indigenous Chicago Blues, including Buddy Guy’s, The Waterhole, Rosa’s, the New Maxwell St. Market, and others on the West Side, the South Side, and the North Side.

“Elder Johnson would love that,” he says. “He did not want his Blues Bus to disappear and he does not want Maxwell Street Blues to be forgotten.”

Rev. John Johnson was a loving husband to Marie and loving father of his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He was laid to rest at a ceremony in Indianapolis on November 13.

0 Comments